Speakers and Acoustics – A Marriage Blog

How is the topic of “room acoustics” similar to the spouse of the Vice-President of the United States? They’re both important but very rarely thought about. But the Vice-Prez and spouse are a married couple, and they influence each other considerably – just like speakers and acoustics. However, this being a contentious political year, I’ll now drop that analogy.

When you think about loudspeakers, do you consider the room acoustics they’re in? These two audio product categories – speakers and acoustics – have a huge influence on each other, to the point where I always mention the co-dependence between them in our acoustics webinars. For those of you with a “what time is it?” mentality (nothing wrong with that, just cut to the chase, please), skip ahead to the Conclusion paragraph. For those of you with a “how does the clock work?” mentality, here’s the clockwork part.

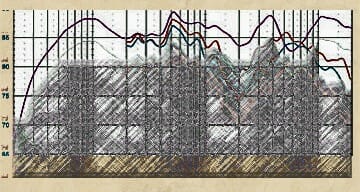

Speakers are mostly omni-directional over much of their bandwidth, meaning the sound spreads out evenly from the speaker at most frequencies in most directions. When a speaker driver – woofer, midrange, or tweeter – reproduces frequencies higher than the quarter-wavelength of the driver’s diameter, those frequencies become more directional, propagating less and less evenly as the frequency rises. Many speaker designs cross over a driver to the next-higher driver before the quarter-wavelength is reached, maintaining omni-directionality (BTW, different parameters apply for dipole and bi-pole designs). And while on-axis frequency measurements (directly in front of the speaker drivers) is how we usually assess performance, the speaker’s “power response” is much more important as a performance indicator.

Power response is the amount of acoustic-power-by-frequency a speaker delivers to a room, and the key word here is “acoustic” – the signal a speaker propagates into the room it’s in, at all frequencies. In many two-way designs, the woofer starts rolling off power as it approaches the crossover point, resulting in less acoustic power in the room at midrange frequencies. And the tweeter also shows this same power-response roll-off at higher frequencies. While a speaker’s on-axis response may look flat, the power response may have significant dips, which will result in a very uneven room response.

Power response is the amount of acoustic-power-by-frequency a speaker delivers to a room, and the key word here is “acoustic” – the signal a speaker propagates into the room it’s in, at all frequencies. In many two-way designs, the woofer starts rolling off power as it approaches the crossover point, resulting in less acoustic power in the room at midrange frequencies. And the tweeter also shows this same power-response roll-off at higher frequencies. While a speaker’s on-axis response may look flat, the power response may have significant dips, which will result in a very uneven room response.

This is important because, in addition to the speaker’s uneven power response, the room adds its own reflective issues – flat wall surfaces bounce the speaker’s signal back to our ears, which causes destructive interference (see our video “How Sound Works (In Rooms)”), but not as much at the power-response dip frequencies. This now makes the acoustic soundfield very uneven in both phase-response (caused by the reflections re-combining to add/cancel with the original sound) and power response.

Conclusion: for most loudspeakers, improving room acoustics – by adding phase-coherent diffusion and a balanced amount of absorption – will greatly improve the speakers’ performance, especially when the speakers have uneven power response. Acoustics can be like a marriage – bad (people or rooms) can make good (people or speakers) bad; bad (people or speakers) can improve with good (people or rooms). And – sometimes it gets complicated.